On Stage - Head Table - The Membership - Blacklist - Visitors

|

Charles Baggs ("Doc")GOLD CLUB Father of the Big Store.

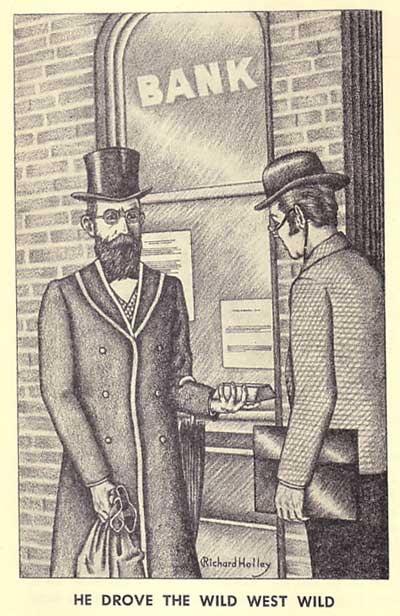

Called by some "King of the Con Men," Charles Baggs is credited with inventing the fake gold brick swindle, and refining the monte store techniques created by his friend Ben Marks, which later evolved into the big store practiced with such efficiency by Lou Blonger's organization. Baggs is said to have been one of Lou's associates, as well as a part of Soapy Smith's operation in Denver. Among pioneer Denver's most fascinating rascals was "Doc" Baggs, adept at selling gold bricks to bank presidents. By turns the populace was shocked, or shaking with laughter at the outlandish activities of this king of the con men, who blandly boasted in the newspapers of his skill at "skinning suckers," and who for six years openly defied Denver's red faced and frustrated lawmen. Shocked or not, Denver secretly was just a bit proud of his outstanding accomplishments as a bunco artist. When Oscar Wilde visited Colorado on his noted lecture tour in 1882, the Rocky Mountain News intimated that when it came to fluency, "Doc" Baggs could make the distinguished visitor look like thirty cents. Forbes Parkhill, The Westerners Brand Book

Parkill spills a bit of ink about the so-called Otero con, already a favorite of ours. In 1882, while the Blongers were in Albuquerque, Las Vegas, NM businessman Don Miguel Otero traveled to Denver, to see Oscar Wilde, as it turns out. Baggs and his cronies took Otero for $2400 in a fake policy shop. The con is notable first and foremost because it played out quite publicly in the papers. What's more, the accounts of the stout efforts of Otero's son, also named Miguel, to recover the funds are a joy to read. It's unsurprising the younger Otero would one day be elected governor of the state. As for the con itself, it's interesting to see an early version of the big store con as played by Baggs, innovating on Ben Marks' lottery shop concept. At the time of the [Otero] visit, lotteries were legal in Colorado and Denver supported many "Policy shops," operating lotteries similar to the modern numbers racket. Colorado derived considerable revenue from the state-operated lottery. In the lobby of his hotel, Don Miguel encountered a young man claiming to be from his home town. The stranger's innocent appearance failed to mark him as a bunco "steerer." He asked the New Mexican to accompany him to a policy shop to learn if he held a winning ticket. On the street they met a friend of the young man. He likewise held a lottery ticket and boasted that he knew a system for beating the game. They found the policy shop in charge of a stocky man of middle age-actually "Doc" Baggs, whom the newspapers had described repeatedly as "unquestionably the most successful confidence man in the West." His hair and full beard were dark brown, he wore green glasses, and a finger was missing from his right hand. At the drawing the young man failed to hold a winning number, but his friend who "knew how to beat the system" won $100. On the next drawing he won again. Pleading that he was short of cash, he proposed that Don Miguel bankroll him in return for a 50-50 split of their winnings. To Don Miguel it seemed a sure thing; an easy way to make a cleaning. Finally the stranger pyramided his winnings to $2,400, but the venerable policy shop operator told him that he could deliver the cash only if the recipients could establish their credit by producing a similar amount as evidence that they could have paid, had they lost. Lacking that much cash, the New Mexico bank president signed a five-day note for the $2,400. When he returned the following day to collect his winnings he was informed that the note had been discounted at a local bank and the money paid to Don Miguel's friend. He never saw the "friend" again, or the money. In a newspaper interview the next day "Doc" Baggs readily admitted the swindle. "I'm a poor man and Otero is rich. I need the money and he can afford to lose it. He dares not squeal or have me arrested for he is a businessman, has served several terms in Congress and is afraid of publicity." The check was given to banker Pliny Rice, who paid some fraction on the dollar to Baggs et al. for the note, which he intended, of course, to cash for face value. The younger Otero had him pinched instead. As for the elder Otero, he was apparently unwilling from the start to publicize his error in judgment — despite the fact that the papers were all over the story — and he never showed to testify, so Baggs walked. "Whenever I see one of those robbers of human nature, who have grown rich from public plunder, but who still desire more, — when I see such men looking into the windows of banks and wishing they could steal the bonds without being publicly disgraced, or gazing into a jeweler's window and thinking how they would like to get away with all the diamonds, I know what with all their cunning and shrewdness they are suckers and an irresistible desire comes over me to skin them. I am emotionally insane. I feel like downing them if I can." The search for Doc Baggs got this wry treatment from the Daily News: Denver Daily News, Wednesday, April 19, 1882 BOLD, BAD BAGGS Sought but Not Found by the Vigilant Police. The Search Full of Interest and Incident. The statement of THE NEWS yesterday morning that the whole police force were engage in hunting for "Doc" Baggs, was strictly correct, and further investigations revealed some rather amusing particulars. The office of Baggs' attorney was besieged till a late hour of the night by policemen and police sergeants, many of them in citizens clothes, who hung around the stairway and in the corridors waiting to find the bold, bad man whom Mr. Lomery thinks is armed with bowie knives and revolvers. The building in which the attorney has his office is a large one and has in it many law and other offices. The police were industriously examining the water closets, hanging around the back stairs and patrolling all parts of the building. One suite of rooms in the building is occupied by a pretty milliner, who has very large and pleasant rooms, and is not often troubled by gentlemen visitors. About 9 o'clock Monday evening she was going into an alcove to retire for the night, when she became suddenly convinced that there was a man in the room. Turning on the gas a little more fully she suddenly recognized a slight-built form in a gray suit. "Whatever do you want?" she shrieked. "Isn't Doc Baggs here?" blustered out the un-uniformed patrolman; "I am a policeman and want to arrest him." "No, sir, he is not, and if you are a gentleman you will leave here at once. Do you hear?" "Yes, ma'am; all right, ma'am," said the man, edging toward the door. Pausing on the threshold he turned and remarked, "Have you a telephone, ma'am?" "Yes, sir, what of it?" "Well, ma'am, if as how the man Baggs comes here to-night and you hear him in the hallway, look out and see if it's him, and then telephone to headquarters. The old Chief says he must have the Doctor, dead or alive, before morning, or off goes his own head. That's what the Mayor tells him." Some of the policemen were bolder in their ventures and nearly all of the whole forty-four called at the office of Baggs' attorney and inquired if the doctor was there, while one of them hung around the door for three mortal hours, and on being asked at the end of that time what was wanted, asked if "Doc" Baggs was inside. One policeman slept in the lawyer's office nearly all night and did not leave till 2 o'clock yesterday morning, when he was fired out by the janitor. A short time afterward he was seen groping about the alley at the back of the office looking for the great bunko-man. Baggs' attorney gave the policeman a letter to Mrs. Baggs, asking her to say to her husband that the police were hunting for him, and that if he would come down town and permit himself to be arrested everything would be all right. Mr. Inman, of the police committee, was hunting after the Doctor till nearly midnight, looking through the blinds into saloons, peering cautiously up stairways and ransacking Lawrence street from Fifteenth to Sixteenth, on the lookout for the man that the police of Denver were unable to capture. Poor Mrs. Baggs was visited by several policeman on Monday evening and all through the day, all begging her to turn her husband over to them. She failed to accede to their very reasonable requests, and the Doctor is still missing. There is little doubt that the Doctor is hiding somewhere, and it is confidently asserted that some of the police know where he is; but he very naturally objects to being arrested at some late hour of the night, when he would be unable to procure bail and would be obliged to spend the night in jail. When the fly cops get tired of hunting for him, he will undoubtedly turn up, go before a Justice, offer bail for his appearance, and boast of the fact that the Chief of Police is the latest sucker he has skinned. I also got a kick out of what Parkhill had to say about Baggs and Wilde: Uncultured Denver was somewhat suspicious of Oscar Wilde's aim to spread culture throughout benighted America. His favorite phrase, "too utterly," aroused the suspicions of rough-and-ready westerners who, accustomed to "Doc" Baggs' con games, saw in the lecture tour an attempt to sell our citizens a cultural gold brick. The following is an excerpt from the "Ode to Oscar," published in the News: When thou talkest of being utter We show up "Windy" Clark who, we will bet Can utter more in the brief circumscribing of a minute than thou canst in a week. If thou dost boast of being too, we will produce Charles Baggs, M. D., who is as too As thou art, and a durned sight tooer. Too Utterly sounds too much like Totally. But what about Baggs and the Blongers? There are anecdotal suggestions that these gentlemen may have worked together, but no evidence. Parkhill tells us Baggs left Denver in 1886, two years before the Blongers came to town for good. But they were in the Denver/Leadville area from 1879 through 1881, and so was Baggs. That they were acquainted can probably be taken for granted. Interestingly, Baggs first came to the area as a young man looking for gold in 1859, at a time Sam may well have been kicking around Colorado as well. Sam and Lou also spent some time in the Council Bluffs area around 1870, when they ran a hotel and billiard room in Red Oak, Iowa. At the time, Baggs was said to be practicing in the area in the company of such as Ben Marks, Canada Bill Jones, George DeVol, Frank Tarbeaux, and John Bull. Here's a perfect example of the twinkle-eyed scoundrel that epitomizes the "All-American bunco man," as Parkhill says he was called. When Sheriff Mike Spangler jailed the doc on a bunco steering charge, the defendant appeared in court as his own attorney, pointed out that the Colorado statutes contained no such term as "bunco steerer," and won a dismissal. Thwarted in his effort to keep the "doctor" behind bars, the sheriff directed a deputy, Emil Auspitz, to follow him everywhere and warn every person he met that Baggs was a notorious bunco man. The "doctor" was delighted by this mark of distinction. Entering his office, he'd switch costumes, emerge disguised, elude his "shadow" and then notify the sheriff that the deputy was loafing on the job. "Send him to the Windsor Hotel," he invited cordially. "I'll be waiting for him there." After the deputy had learned how effectively Baggs could disguise himself, one of doc's cappers would point out to the officer some stranger, confiding that it was the bunco man in disguise. Following the innocent man, the deputy would warn every person that the stranger met that this was the notorious "Doc" Baggs, much to the delight of the "doctor," who'd be shadowing the shadow to watch the fun when the indignant stranger punched the deputy's nose. More to the point, here we see that "code of ethics" that, at least fictionally, distinguishes the true confidence man. Upon Baggs' return to Denver he learned that one of his henchmen, Tom Daniels, was in jail for robbing Senor Francisco Gonzales while the senor chanced to be drunk. Baggs, described by a newspaper as "this distinguished and oleaginous disciple of Esculapius," was humiliated that Daniels would violate the ethics of his profession, and assured a reporter that money enough can be made by turning tricks on the square basis." The reporter commented, "This sentiment may be forced." Fact is, most of the con men we've run into would just as soon cheat you bald-faced and then threaten you if you don't just take it like a sucker. Baggs left a different impression. Yet another interesting swindle: A bearded miner called upon a prominent attorney, seeking aid in locating a lost partner. "Several years ago he got into trouble and disappeared after killing a man," was the explanation. "Since that time the mine has become a rich producer. I've been offered several hundred thousand dollars for the property but I can't sell without the signature of my missing partner." He produced a letter confirming the offer to buy the mine. Displaying a roll of bills totalling several thousand dollars and a money belt stuffed with gold nuggets, he asked the lawyer to recommend a bank where the money could be deposited and the gold left for safekeeping. Convinced of the stranger's responsibility by this display, the lawyer placed a number of advertisements in western newspapers asking the missing partner to communicate with him. In the course of time he received an answer, the whereabouts of the writer concealed by a "blind" newspaper box number. Considerable correspondence ensued, the missing partner stating that he feared to make his whereabouts known because of the murder charge against him. He offered to sell his onehalf interest for $50,000 if he could remain in hiding and merely sign the necessary papers. The lawyer's bearded client was distressed because he lacked the $50,000 necessary to buy out his partner, but offered to put up $25,000 if the lawyer could raise the remainder. Scenting a chance to make a quick and fat profit, the lawyer put up the $25,000 and never saw his money again. Baggs, of course, was both the client and the missing partner. What happened to Baggs and his wife, Tout (why not?), in whose name Baggs kept his ill-gotten gains? Although jailed on countless occasions, available records fail to show that "Doc" Baggs was never convicted of a bunco game charge. In 1915, a Denver newspaper reported that the wily doc, then in his seventies, had "turned his last trick," retiring to his California ranch after skinning a sucker of $100,000. Baggs is also remembered for the imposing iron safe in his office. It was actually made of wood, and folded to the size of a suitcase, but served its purpose: assuring the mark that the office was legitimate and financially sound. |